We’ve finally moved on from the Fathers of the Church, and we find ourselves in the Dark Ages. But no worries, because as dark as they might have been, there were many great lights! Which leads us to St. Bede the Venerable, the Doctor Anglorum (English Doctor).

Not much is known about Bede’s life, but he fills us in from his own writings. He was born around 672 in Northumbria, northeast England. At the age of seven, Bede’s parents entrusted him to the Benedictine monastery to receive an education. With the Roman educational structure destroyed in Europe, monasteries were the place to be! We don’t know whether he intended to be a monk when he entered at such an early age, but that’s how it ended up. His exceptional abilities and dedication to the monastic rule led him to being ordained a deacon earlier than normally allowed, and he was ultimately ordained a priest at the age of 30. Although he travelled around a bit, most of Bede’s life was spent in the monastery. He died there on May 26, 735 (the Feast of the Ascension), lying on the floor of his monastic cell and singing the Glory Be.

Not much else is known about his life, but we have a lot of his works. Bede wrote many Scriptural commentaries and some scientific treatises. He also helped write several teachers’ manuals for grammar school, and dabbled in poetry.

But what St. Bede is known for most of all is his Ecclesiastical History of the English Peoples. This was a compilation of five books regarding the geographical makeup and history of England, beginning with Julius Caesar’s invasion in 55 BC and stretching all the way up to his present day (731 AD). Interestingly, one of his unheralded contributions within this work was his dating system. While most writings at the time dated events as “during the reign of so-and-so,” Bede chose to refer to “the year of Our Lord,” or Anno Domini (AD). While Bede didn’t come up with this form of dating, his use of it made it mainstream, even to the present day!

Bede’s Ecclesiastical History is one of the main sources for what we know of English history today. It includes the story of St. Alban, the first British martyr (although a different one from the namesake of our neighbors), the mission of St. Augustine of Canterbury, who brought Christianity to the Anglo-Saxons, and a description of the kings of Dark Age England in a time where there were very few details. Bede even describes the military victory at Badon Hill by Ambrosius Aurelianus, a guy some people say became known by a different name – King Arthur!

St. Bede the Venerable finds a special place in my heart because of my love for Church History. For Bede, history was more than just relating the events that have happened in the past, because honestly, that can get pretty boring. Church History offers an opportunity for us to look back to see the way the Holy Spirit has been weaving through our human experience. Hopefully these articles are not just a collection of stories and interesting facts, but can help you see the way God is working through his people!

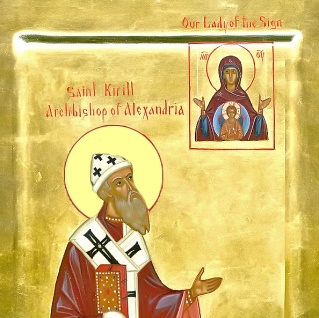

Who would have thought that the name “Cyril” would be such a popular one in the early Church? We had St. Cyril of Jerusalem before, and now we continue with our Doctors of the Church with St. Cyril of Alexandria.

Who would have thought that the name “Cyril” would be such a popular one in the early Church? We had St. Cyril of Jerusalem before, and now we continue with our Doctors of the Church with St. Cyril of Alexandria.